Defining Freedom

Last semester I co-taught a class on American history since the Civil War. Throughout we emphasized a central theme: the changing meanings of freedom. In a prelude to the lectures on the Great Depression, we asked the class (mostly first-year Irish students, with a smattering of visiting international students) to take a few minutes to write individual responses to two prompts:

- Define freedom.

- Can meaningful freedom exist in a situation of extreme inequality?

Their varied answers gave me a lot to think about, particularly in comparing current political perspectives and goals in the US versus Europe.

The definitions of freedom fell along a spectrum from what I think of as individual to social freedom. In that roughly order and in condensed form, they included:

- The right to live on your own terms

- Ability to do completely as you like with no repercussions / limitations

- Ability to do as you like within the limits of the law / reason (as long as that law is democratically established)

- Ability to choose how to live, act, and speak without oppression, discrimination, or fear

- Ability to achieve a fulfilled life, in which all basic needs are met and personal progress can be attained

- Ability to do as you like and go where you please as long as you obey rules and laws that protect other people’s freedom

- Democratic government and enfranchisement

- Rights: vote, speak, practice any religion, safety, health, property, basic human rights

- Equality: Ability to pursue opportunities (education, careers, wealth, property, government, etc.) regardless of race, gender, sexuality, faith, or culture

Somewhere between the individual and the social there is a shift from singular to plural; as the definitions move along the spectrum other people gradually begin to enter into the equation.

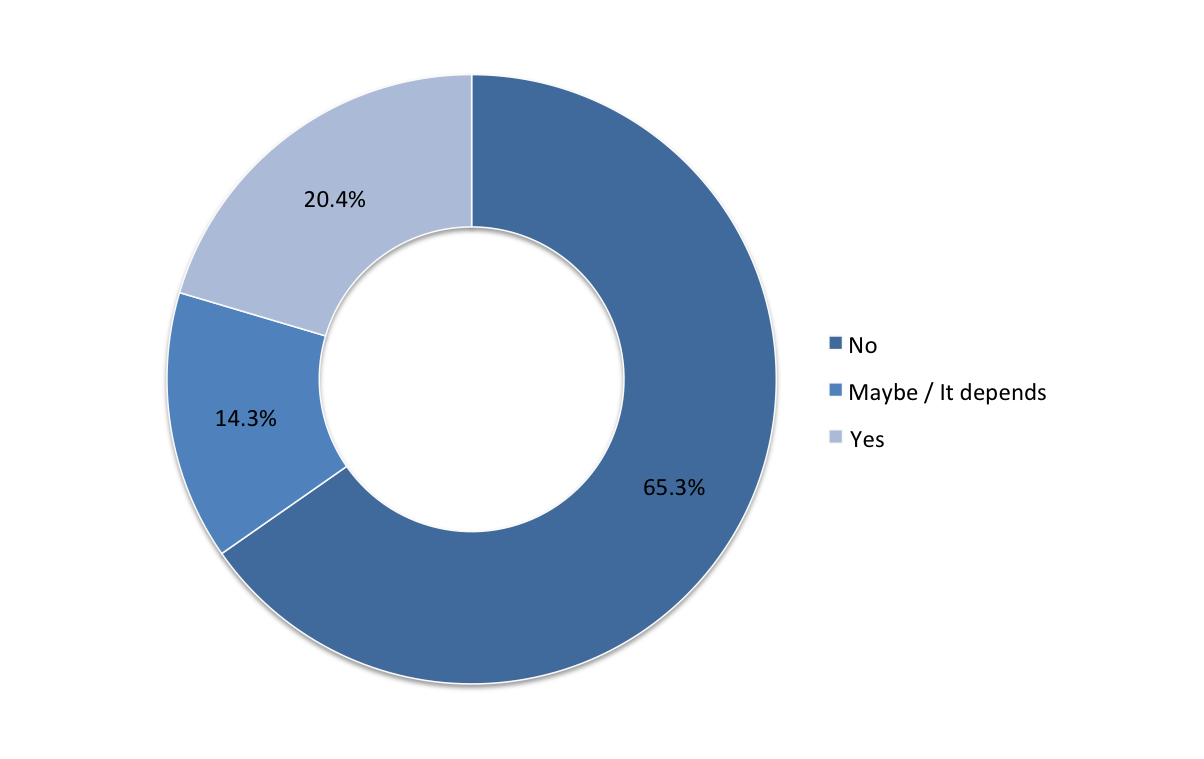

The shift became even more apparent in the responses to the second prompt. Not all the students gave an exact yes or no, but I categorized their answers for the chart below:

Even many of those choose yes or no also qualified their answers. On the no side, they argued that inequalities inhibit freedom, because not all members of the society have the same freedoms in practice. Many of those who said yes added that freedom might still have limitations when there are extreme inequalities. In between, they said it depends on the nature or extent of the inequalities or that some types freedoms may exist (e.g. freedom of speech), but not necessarily meaningful freedom overall.

This was not a comprehensive survey, but from discussions with students and friends (surveyed even more informally) I got a sense that if combined with demographic data on nationality, political views, or socio-economic background the results would be even more interesting. It strikes me that the ‘individual’ conception of freedom, and the idea that it therefore can exist even alongside inequalities, is more characteristically American. The European welfare state idea – and the government influence it involves, which many Americans are quite hostile to – is based more on the freedom-as-equal-opportunities definition. Each has emerged from a unique set of historical and social circumstances.

As ways of thinking, these ideas suffuse our national collective mentalities. They pervade our political discourse. In the United States I think it would take more than legislation to successfully adopt social programs such as public healthcare or free education: it would take a shift in mindset and a commitment to a broader definition of what it means to be free.

Thanks to Sarah Thelen for being an awesome co-teacher and for comments on a draft of this post!