The Dustbin of History

I am now contributing to a new collaborative history blog, The Dustbin of History. Please visit, browse, read, and comment!

I am now contributing to a new collaborative history blog, The Dustbin of History. Please visit, browse, read, and comment!

‘The Irish Famine in Historical Memory: A Comparison of Four Monuments’, from The Dustbin of History, 1 April 2013.

Though without doubt a seminal event in Irish history, the meaning and memory of the Great Famine of 1845-9 remains contested. It is estimated that over 1 million people died and 2 million emigrated and it catalyzed emigration for the rest of the century. While historians debate exact figures and the evolution of the historiography of the event, its complex legacy in historical memory, especially across the vast diaspora, remains underemphasized. A comparison of four memorials, one in Canada, two in the United States, and one in Dublin, offers some insights. As Ian McBride writes, ‘we need to scrutinize collective myths and memories, not just for evidence of their historical accuracy, but as objects of study in their own right’.[1] These monuments are a physical manifestation of those ‘myths and memories’ and can be read as visual, cultural sources. First, an introduction to each monument, then some reflections on them.

Grosse Île, Canada

A 46-foot high Celtic cross stands at the highest point of this three by one mile island in the St. Lawrence River, thirty miles downriver from Quebec. Grosse Île served as a quarantine station for incoming immigrant ships from 1832 and witnessed the terrible devastation wrought by famine and disease on the ‘coffin ships’ that brought Ireland’s destitute to the New World in the late 1840s. Michael Quigley estimates that between 12,000 and 15,000 from the Famine era are buried here.[2] This monument, the first of its kind, was paid for by public subscription raised by the Catholic, nationalist organization the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH).[3] It was unveiled on 15 August 1909 in a ceremony attended by 9,000 people, including the last surviving priest who had attended the sick and a woman who had been orphaned there as a young child and adopted by a local family. Now, the whole island is a National Historic Site and many other commemorations have taken place there.

The inscription on the cross reads:

Cailleadh Clann na nGaedheal ina míltibh ar an Oileán so ar dteicheadh dhóibh ó dlíghthibh na dtíoránach ngallda agus ó ghorta tréarach isna bliadhantaibh 1847-48. Beannacht dílis Dé orra. Bíodh an leacht so i gcomhartha garma agus onóra dhóibh ó Ghaedhealaibh Ameriocá. Go saoraigh Dia Éire.

Children of the Gael died in their thousands on this island having fled from the laws of foreign tyrants and an artificial famine in the years 1847-48. God’s blessing on them. Let this monument be a token to their name and honour from the Gaels of America. God Save Ireland.

Famine Memorial, Washington Street, Boston

This memorial by Robert Shure was unveiled in June 1998 as part of the 150th anniversary of the Famine. It consists of a small round plaza with eight plaques describing the historical context and in the middle of the space are two groups each with three bronze figures, a man, a woman, and a child. In the first group, the man sits, head hanging limp and bones showing through his skin, while the woman kneels looking upward with one arm raised, with the child beside her. They are clothed in rags and emaciated. In the second group, all three figures are standing and they appear in motion, as if striding forward, healthy and well-clothed, but the woman has her face turned back, looking at the first group.

Irish Hunger Memorial, New York City

Designed by artist Brian Tolle and opened in 2002 this is perhaps the most ambitious and diverse of the four memorials here. The structure looks like an Irish hillside. A passage under it is reminiscent of ancient tombs like Newgrange. Above, the landscape incorporates the ruins of a nineteenth-century stone cottage from transported over from Mayo, surrounded by native Irish plants and inscribed stones from every county. From the top visitors look out over the Hudson River and the Statue of Liberty. The sculpture sits on an valuable piece of real estate, to south is the New York Mercantile Exchange, and the artist says that seen from this context it’s ‘an extraordinary thing’ that visitors ‘look out on an abandoned Irish field that’s here to commemorate a traumatic event in terms of world hunger’.[4]

Famine Memorial, Custom House Quay, Dublin, Ireland

Erected in 1997, this monument designed by sculptor Rowan Gillespie marks the site of departure of many emigrant ships. It takes the form of bronze figures, all emaciated and ragged, grasping bundles in their arms and walking towards some unknown future. On a wet, gray day, these figures appear eerie and unnerving. I am told that a sound instalation on the site used to play looped recordings of a voice reading lists of the food exported from Ireland during the Famine (though I don’t believe this was the the case when I visited). Nearby is the World Poverty Stone, expressing solidarity with people living in poverty across the globe, its proximity situating the Irish Famine as a lesson for understanding human rights today.

Why compare these? What can we learn from them? They commemorate the same event, but in quite different ways and in doing so I think they reveal much about how and why the Famine is remembered in Ireland and the Americas and why its meaning remains contentious. The first, the monument at Grosse Île evokes the ethos of its era, both in standing and inscription: the imagery of the Celtic Cross is one of a grave marker but in a form that brings to mind a Gaelic, Catholic golden age, while the plaque on it ties into the idea of Famine emigration as forced exile and the nationalist interpretation of the event and conditions that produced it as the work of ‘foreign tyrants’. Kerby Miller writes that in the aftermath of the Famine, Catholic clerics and nationalist politicians (both opinions represented in the AOH), ‘generalized the people’s individual grievances into a powerful political and cultural weapon against the traditional antagonist’.[5] In America they did so particularly effectively, not only because of memories of terrible suffering in Ireland and with no choice but emigration, but perhaps also because in the New World they faced prejudice and discrimination, which kept them as a group largely disadvantaged and left them bitter and disillusioned.[6] Nationalist readings of the Famine, represented by the opinions of John Mitchel and the AOH cross at Grosse Île, offered an explanation for their suffering as well as a ‘redemptive solution’ by calling on them to unite in recognition of their proud heritage, made mockery of by both the British government and American nativists.[7] The first memorial thus is both commemorative, marking the last resting place of thousands, and a strong signal of the strength of Irish nationalist sentiments in Canada and the United States.

The monuments in Boston and New York convey similar messages, albeit in slightly different ways. In the Boston memorial, the two groups of figures seem to be of the same people, a ‘before and after’ portrait of emigration. The first group, foresaken and emaciated leaving their native land, the second, healthy and successful in their new lives, though the female figure glances over her shoulder at the former. However, this sort of progress in the New World often took multiple generations and those who succeeded did not always choose to look back at where they had come from, viewing the Famine with shame or as part of the baggage of a past best left behind. Nonetheless, that story of ‘rags to riches’, of ‘No Irish Need Apply’ to the election of John F. Kennedy, has proven powerful regardless of its truth or complications. Not all immigrants found prosperity in America, but the enduring mythology is of those who did. As Kevin O’Neill writes, ‘The Famine provides Irish Americans with a “charter myth” – a creation story that both explains our presence in the new land and connects us to the old via a powerful sense of grievance.’[8] The Irish Hunger Memorial in New York emphasizes this point: the sense of grievance encapsulated in the abandoned, ruined cottage on an overgrown and rocky hillside, and the presence and success in the new land in the surrounding skyscrapers and view of the Statue of Liberty, the symbol of American opportunity.

The Famine Memorial in Dublin, in contrast, conveys an image of starvation, hopelessness, and tragedy. Who are these people? Where are they from? Where are they going? Will they even make it there? Their bodies are emaciated, their faces vacant. They show no signs of anger or resistance. It is a representation of the starving poor of Ireland leaving their country while food is also exported from along the same quays. Though it draws on nationalist sentiments similar to those found in North America, unlike its counterparts this memorial contains no suggestion of positive opportunity or triumphalist vision for these people. However, its proximity to the ‘World Poverty Stone’ does relate to the message emphasized by Mary Robinson during her presidency and in her speech at Grosse Île in 1994, that we should recognize the connection between human suffering in the past and that in the present. She said we must choose between being ‘spectators’ or ‘participants’, between separating ourselves or being compassionate and involved.[9] She rejected any moral distancing or dispassionate analysis, instead choosing to see the human element of the past and to understand it in contemporary terms.

These physical memorials each in a sense embody the ethos of the time and place that produced them and its historical memory of the event. Overall they suggest that for those in Ireland, the Famine continues to evoke memories of shame, hopelessness, and suffering, and while people such as Mary Robinson have, after 150 years, come to use it as a lesson for the present, that has not changed the persistent image in national consciousness. The memorials in Canada and America suggest a very different type of historical memory: for members of the Irish diaspora the Famine was not just a tragedy to be commemorated, but one from which they rose despite hardships, their creation story. These latter memorials contain a greater sense of optimism, a reminder of how far they had come. While the Irish nationalist historical narrative on both sides of the Atlantic used the Famine as proof of British misrule, the story of its casualties has gone down divergent paths.

[1] Ian McBride, ‘Memory and National Identity in Modern Ireland’, in I. McBride (ed.), History and Memory in Modern Ireland (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001), p.41.

[2] Michael Quigley, ‘Grosse Île: Canada’s Famine Memorial’, in A. Gribben (ed.), The Great Famine and the Irish Diaspora in America (University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, 1999), p.150.

[3] Ruth-Ann M. Harris, ‘Introduction’, in Gribben (ed.), The Great Famine and the Irish Diaspora in America, p.12.

[4] RTÉ, Blighted Nation [radio programme], Episode Four, January 2013. For a longer discussion and interpretation of the Irish Hunger Memorial in New York see: Marion Casey, ‘Exhibition Reviews: The Irish Hunger Memorial, Battery Park City, New York’, Journal of American History, vol.98, no.3 (2011), pp.779-782.

[5] Kerby Miller, ‘“Revenge for Skibbereen”: Irish Emigration and the Meaning of the Great Famine’, in Gribben (ed.), The Great Famine and the Irish Diaspora in America, p.185.

[6] Ibid., pp.189-90.

[7] Ibid., pp.189-90

[8] Kevin O’Neill, ‘The Star-Spangled Shamrock: Meaning and Memory in Irish America’, in McBride, History and Memory in Modern Ireland, p.118.

[9] In: Peter Gray, The Irish Famine (Thames & Hudson, London, 1995), pp.182-3.

Update 19 June 2014: for further reading also see Emily Mark Fitzgerald, Commemorating the Irish Famine: Memory and the Monument (Liverpool University Press, 2013) and Margaret Kelleher’s lecture ‘Hunger in History: Monuments to the Great Famine‘ and article of the same name in Textual Practice, vol.16, no.2 (2002).

A blog post over on The Dustbin of History, 18 March 2013.

Go deó deó rís ní raghad go Caiseal

Ag díol ná reic mo shláinte;

Ná ar mhargadh na faoire am shuighe cois balla,

Um sgaoinsi ar leath-taoibh sráide:-

Bodairídh, na tire ag tígheacht ar a g-capaill

Dá fhiafraidhe an bh-fuilim h-írálta,

Téanamh chum siubhail, tá’n cúrsa fada

Seo ar siubhal an Spailpín Fánach!

No more – no more in Cashel town

I’ll sell my health a-raking,

Nor on days of fairs rove up and down,

Nor join in the merry-making.

There, mounted farmers came in throng

To try and hire me over,

But now I’m hired, and my journey’s long

The journey of the Rover![1]

This song from the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century tells the story of ‘an spailpín fánach’, ‘the wandering labourer’, who hires himself out to farmers to make his living, though in this case he has chosen to forsake that life and all its hardships. Seasonal migration, both within Ireland and across the Irish Sea to Britain, formed an important part of the life cycle of many rural communities over the centuries, probably peaking in the decades immediately after the Great Famine. An estimated 38,000 migratory agricultural labourers went to Britain in 1880, and 27,000 in 1896, but numbers dropped to 13,000 in 1915, after which the government stopped collecting the statistics.[2] Despite evidence that it did continue (though in smaller numbers) even until the 1980s, little work has been done specifically on the twentieth century.[3] The event that garnered the most notice was a tragedy in September 1937 when ten workers from Achill Island died in a fire in a bothy in Kirkintilloch, Scotland. This prompted the establishment of the Irish government’s ‘Inter-Departmental Committee on Seasonal Migration to Great Britain, 1937-1938’, which produced a report describing the categories of labourers, primary places they came from, and recommendations, but little consideration has been given to the persistence of seasonal migration after that time.[4]

The voices of a few former migrants can be heard on the RTÉ radio documentary, ‘The Tattie Hokers: The Migrant Workers of North Mayo’. As one man says on the programme, seasonal migration was ‘a way of life’ for many, though it seems one relatively neglected in scholarly works on migration and the Irish diaspora. The most comprehensive work on the subject is Anne O’Dowd’s Spalpeens and Tattie Hokers: History and Folklore of the Irish Migratory Agricultural Worker in Ireland and Britain. However, it is organized thematically rather than chronologically, thus integrating oral testimonies and answers from folklore questionnaires related to twentieth-century movement with other similar material from earlier periods. This emphasizes continuity over change, minimizing consideration of questions such as: Did mechanization of farm work have a significant effect and how? Did seasonal migration continue but in other lines of work (outside agriculture)? How did the changing political context (Ireland’s independence, the two world wars) affect workers’ experiences? What were significant regional differences? Did certain localities continue to have greater seasonal movement and why?

I can’t claim to answer all those questions, but my interest in them was prompted by anecdotes in two oral history interviews. Fiddle player Vincent Campbell was born in 1938 in An tSeanga Mheáin near Glenties, Co. Donegal. The county has a long history of ties to Scotland and Vincent describes workers going for the ‘tattie hoking’: ‘There was an awful lot of potatoes grown in Scotland that time and when it would come to, say, around the month of October, the spuds would be, the potatoes would be raked down to be packed and there used to be gangs would leave Donegal here and go over to Scotland to gather the potatoes.’[5] He recalled gangs still engaging in this type of work in his youth:

Sara Goek: Did you know many people that went over to work in Scotland in your time?

Vincent Campbell: Of course I did know them. The last of the crowds that I heard of going over when I was young they came from Glenfin country, that’s up near, that’s just about, I suppose it would be about eight miles from here [Glenties]. They were the last that took gangs with them going over to Scotland. There was other places then down Gaoth Dobhair and places like that, they used to have a gang. They had to try to have a ganger man or a gaffer of some kind as well, but a lot of them they enjoyed going over because there was great dances on the Friday night always, they would have great dances. So it was entertaining as well. If a fiddle player would hear or a musician would hear that they were going to go on such a day, he would make sure to land at their house the night before to tell them, ‘give me a promise – bring back a good tune or a few tunes or a few good songs’ and that was a part of the bargain, that they would have to bring something like that back.[6]

The Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Seasonal Migration specifically mentions this region around Glenties as one of the principal places from which migration took place, with 1,352 agricultural workers leaving in 1937.[7] Vincent’s interest in the subject is also closely connected to the cultural exchange promoted by this type of back-and-forth movement and to this day the Donegal fiddle repertoire retains its influence. Vincent himself worked on a hydroelectric scheme in Scotland when he first emigrated in 1956, following the same route as those before him, and he describes a similar social life with music and dancing on the weekends. However, despite his drawing parallels between the experiences of earlier migrants and his own, the fact that he engaged in industrial rather than agricultural labour shows the declining importance the latter as the twentieth century wore on.

Another musician, Tommy Healy, a flute player from Montiagh, Co. Sligo then living in London, was interviewed by Reg Hall in 1987-88 for his research on Irish music and musicians in London. This area near Tobercurry is also mentioned specifically in the Report as one of those sending large numbers of seasonal workers to Britain, 352 in 1937.[8] Tommy’s narrative of migration is especially interesting because it is multi-generational: his maternal grandfather worked as a seasonal agricultural labourer in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire in the late nineteenth century, his paternal grandfather worked as a hired labourer within Ireland, his father went to Scotland once picking potatoes but then immigrated to Boston (where Tommy was born) around the turn of the twentieth century, the family returned to Sligo in 1928 where they took over his mother’s parents’ farm, and Tommy went to England in 1943, first doing seasonal agricultural work and eventually settling in London after the Second World War, working on railways and in construction. He thus situates his own migration intimately within that of his family and local community, highlighting the normalcy of this type of global transiency, saying of seasonal employment, ‘that was the only employment those people used to have outside their own little farms’ and of going to America and back, to Reg’s astonishment, ‘it was the usual procedure’ and several other families in his parish had done the same.[9]

Tommy’s story differs from those who went before him because he emigrated during the Second World War. He describes the process of getting work in England at that time (listen to part 1 of the interview online, this portion is at 1:14:30):

Reg Hall: Did you do farming work?

Tommy Healy: Oh I did in the early part. That was the only way we could get over here, as a migratory agricultural worker.

Reg: Can you explain that system? This was at the end of the war?

Tommy: No, no middle way in the war really or even 1941 or ’42. In the area that we come from, we were given employment on this piece production and they didn’t want anybody to leave. They wouldn’t give you a permit at the Labour Exchange to leave – you had to get permission, but when it come to harvest time and that if you could prove that you were a migratory agricultural worker, then you got your permission.

Reg: You could prove that in Ireland?

Tommy: Yeah.

Reg: How did you prove that then?

Tommy: Forgery.

Reg: [Laughs] prove that you’d done it regularly, you mean?

Tommy: Yes, that I was there the year before and that this farmer wanted the same men as he had the year before. Somebody that was working in Lincolnshire, that was the principle part of the agricultural work, one of our own mates sent a letter to this one and that one and so on, 4 or 5 letters, such a one wants the same gang, you, you, and mention the names that he had last year. We were never there before, but the bloke in the Labour Exchange or the guard’s barracks didn’t know that. He had to do his own part before you could apply for the passport. The application for the passport had to be done in the guard barracks. He had to sign his name to it and all.[10]

He says ‘forgery’ in a perfectly straight tone of voice, again suggesting it was nothing unusual. During the war the Irish government placed a ban on the migration of men with experience in agricultural or turf work; ‘they didn’t want anybody to leave’.[11] However, despite the complexities of the regulations it seems loopholes existed and the workers proved particularly adept at finding them:

Complicated as the rules for travel and employment may have appeared at first sight, they do not appear to have hindered migration by reason of their incomprehensibility. On the contrary, Irish workers were found to display so considerable a familiarity with the finer points of official requirements, and so ingenious a knowledge of the limits of tolerance which official routine was accustomed to observe, that a constant watch was needed to prevent the evasion of rules.[12]

In the end, Tommy did not migrate with the permit he received through ‘forgery’ because of other circumstances at home, but about a year later he got work through an agent and went over to Gloucestershire:

The next best thing, I had got the passport this time, the next best thing was to sign on with an agent to do agricultural work here. You couldn’t get the work yourself because in wintertime you see it’s thrashing, hedging, all that type of thing, so I signed on and I come over here in the month of February in the middle of a blizzard. But like we got here today and we went off to the food, somebody took us to the food office, the labour exchange and everything, all the paperwork was cleared up that day, and we were out on our glory at seven o’clock the next morning into some farmer’s yard.[13]

He went on to describe conditions in wartime England: working hours (54 hours per week plus overtime), wages (£3 5s. plus a lodging allowance), blackouts (‘no lights whatsoever’), shortages (‘razor blades were hard to find’) and rationing.[14] He did that work seasonally for about three years, going back home to Sligo at Christmas, went back to stay from 1947 to 1949, but then returned to settle in London, where he still lived at the time of the interview.

These two individuals offer only a brief glimpse of patterns and circumstances of seasonal agricultural migration from Ireland to Britain in the twentieth century. They both suggest continuity of geographical patterns, but changes in the type of work and circumstances from their parents’ and grandparents’ generations. Much more work remains to be done to understand these migrants’ varied experiences and contexts.

[1] Traditional song, in Anne O’Dowd, Spalpeens and Tattie Hokers: History and Folklore of the Irish Migratory Agricultural Worker in Ireland and Britain (Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 1991), p.313-6.

[2] Enda Delaney, Demography, State and Society: Irish Migration to Britain, 1921-1971 (Liverpool University Press, Liverpool, 2000), p.28; Appendix II, Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Seasonal Migration to Great Britain, 1937-1938 (Stationary Office, Dublin), p.59. The report estimates that 9,500 seasonal labourers went to Britain in 1937. The 1954 report of the Commission on Emigration and Other Population Problems mentions seasonal migration only in passing in four separate paragraphs.

[3] O’Dowd in Spalpeens and Tattie Hokers provides snippets of evidence of seasonal agricultural labour in the twentieth century: in Connaught ‘‘the tradition continued right up to the 1940s and 1950s’ (p.82), ‘men and women from Ballina and Mulraney, Co. Mayo, still work as tattie hokers in the 1980s’ (p.199), and resentment of Irish migratory workers because of they had not fought in either world war (p.267), but she provides little further detail apart from citation of her own interviews. Many folklore sources were collected in the twentieth century, but it is difficult to pinpoint the time period in which they originated.

[4] The report itself does not actually say the committee was established in response to the Kirkintilloch tragedy, but the letter at the beginning states the committee was appointed on 23 September 1937, exactly one week after the event. For a more detailed description of that particular event see: www.theirishstory.com/2012/09/24/the-kirkintilloch-tragedy-1937

[5] Vincent Campbell, interview with Sara Goek, 12 June 2012.

[6] Ibid.

[7] 9,783 agricultural workers migrated from certain areas of Clare, Connaught, and Donegal in 1937 and Glenties had the 3rd highest total of all the areas enumerated. These areas tended to be in the ‘Congested Districts’, with high population density on poor land and generally small landholdings. Appendix V, Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Seasonal Migration to Great Britain, 1937-1938, p.62.

[8] Appendix V, Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Seasonal Migration to Great Britain, 1937-1938, p.62.

[9] Tommy Healy, interview with Reg Hall part 3, 6 April 1988, British Library. He talks about the work his grandfather would have done as a hired labourer from 04:30.

[10] Tommy Healy, interview with Reg Hall part 1, 28 Oct. 1987, British Library.

[11] A.V. Judges noted in his report, Irish Labour in Great Britain, 1939-1945 (1949), that this ban did not extend to the ‘Congested Districts’ in the western part of the country and though maintained, it had little effect until restrictions were tightened further in 1944 (p.13). There were three ways of securing labour in Britain during the war: through a liaison officer, through direct contact with the employer, or through the employer’s agent. Tommy’s story falls under the second category, of which Judges writes, ‘an employer who was actually in contact with a potential employee could furnish him with a letter… through the Ministry of Labour and the Department of Industry and Commerce and the worker would then secure the necessary travel documents on producing the letter’ (p.14).

[12] Judges, Irish Labour in Great Britain, p.15.

[13] Tommy Healy, interview with Reg Hall part 1, 28 Oct. 1987, British Library.

[14] Ibid.

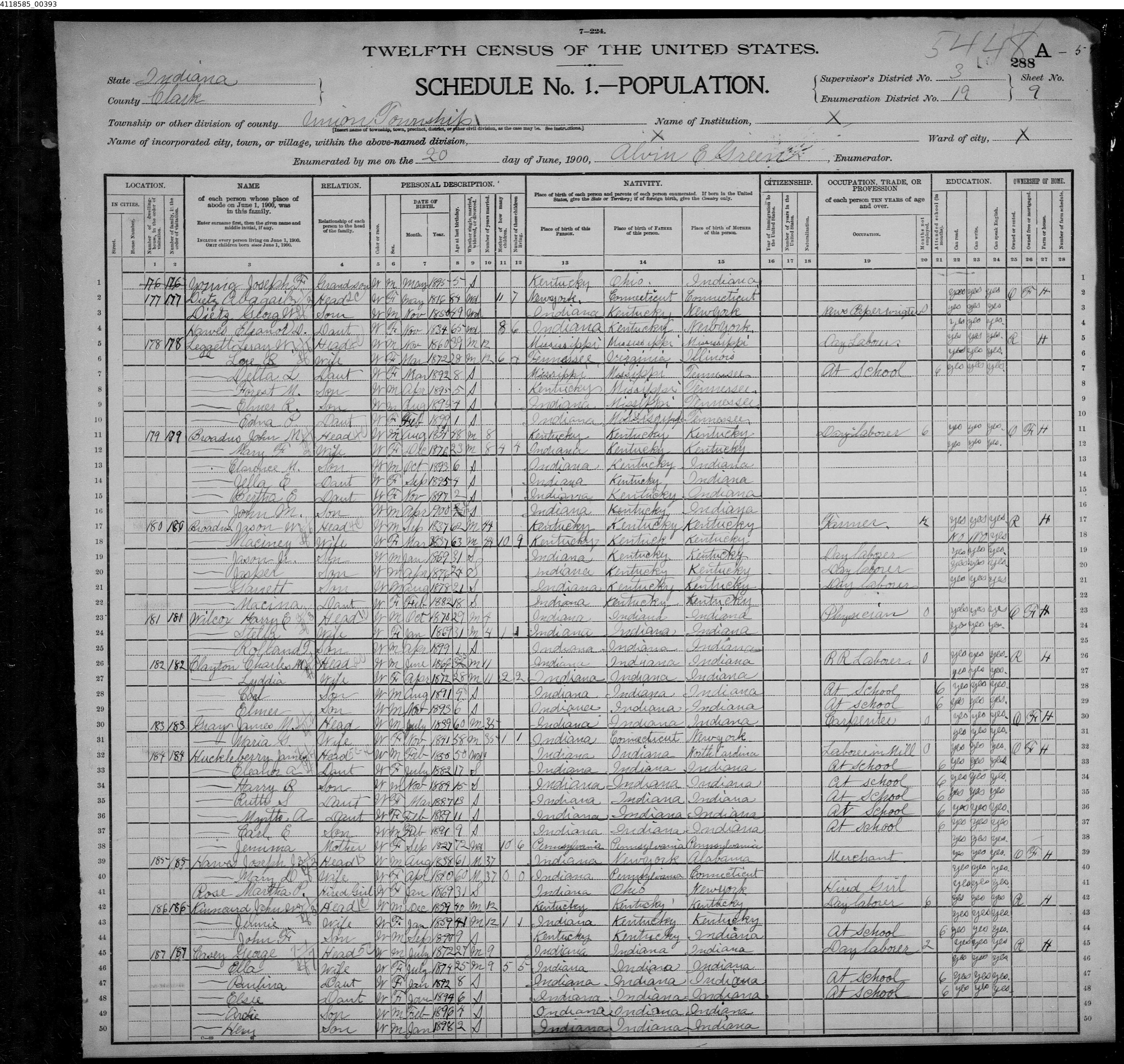

My mom and aunt came to visit over Christmas and at some point, in between all the eating and shopping and walking that we did, we started talking about their father, which led to a discussion of that whole side of the family. I’ve never had much of an interest in genealogy for its own sake, but looking at census records and other sources provided a few hours entertainment and some interesting findings and observations.

My mom and aunt came to visit over Christmas and at some point, in between all the eating and shopping and walking that we did, we started talking about their father, which led to a discussion of that whole side of the family. I’ve never had much of an interest in genealogy for its own sake, but looking at census records and other sources provided a few hours entertainment and some interesting findings and observations.

Despite the amount of records and detail available through online resources (e.g. familysearch.org and ancestry.com) – names, birth dates, death dates, occupations, marriages – what I found most lacking in the whole experience were actual lives and personalities. A few bits of family lore have survived relating to some of the people in the family tree, but for the vast majority the impersonal documentary records are all that I know about them and there is nothing to truly give them context. Given a choice I’d prefer stories passed down with all the colors of everyday life and distortions of time over any amount of statistical detail.

However, it was interesting to try to match popular family stories and perceptions with the discernible facts, particularly relating to ethnic origins. I’d always heard growing up that of my four maternal great-grandparents one was Anglo-American, one Welsh, one German, and one Irish, but how far back those roots went wasn’t always clear. The English goes back to the 1630s – we knew that. If there was indeed a Welsh connection (names suggest it’s likely), I couldn’t find it so it goes back to at least the early 18th century. The German (Bavarian, actually) and Irish connections both date to immigrants who arrived in North America in the 1840s, so my great-grandparents on those branches of the family were both third generation. However, the perception of them as ‘German’ and ‘Irish’ despite the actual distance from those roots suggests the families held on to a relatively strong sense of ethnic identity. It is also interesting that when those two branches of the family came together the German traditions seem to have predominated, like celebrating St. Nicholas Day. My mother was conscious that she had an ‘Irish’ grandmother, but the family never claimed that identity and neither do I. (My standard answer to the question ‘do you have Irish family/ancestry?’ is no, because it has nothing to do with who I am or why I live in Ireland.)

This raises the issue of genealogy leading to the creation of family myths or identities where none existed before. Perhaps some who do genealogical research are motivated by the desire to have a family story where it had been largely lost or forgotten, but while in some ways the impulse is understandable, it can be dangerous in that ‘histories’ enter a story they were never part of before. Thus, people find out that they had ancestors in Ireland in the early 19th century and all of a sudden call themselves Irish, though they may have grown up knowing little or nothing of that heritage or traditions. I find that idea very strange, but maybe it’s a personal issue.

For six weeks this autumn I am tutoring third year students for a core module titled Historical Debate. The key focus of this module is not the content of history, but historiography – how history is written and used, by whom, why, and how those elements change over time. These are central issues in historical research but can be extraordinarily difficult to convey to students. They still tend to want to think of history as ‘what happened’, as an objective perspective on the past, rather than something constantly written and rewritten.

This week they began the section of the course on modern Irish historiography, with particular focus on historical revisionism, so I assigned some background reading, the introduction to D. George Boyce and Alan O’Day’s book, The Making of Modern Irish History: Revisionism and the Revisionist Controversy. Overall it provides a fairly good survey of the issues and developments in twentieth century Irish historiography. I’ve studied revisionism before, but in preparation for the tutorials then I decided to brush up and look more closely at the sources mentioned in that chapter, which led to an interesting discovery (as I put on my Sherlock Holmes hat for Halloween!).

Boyce and O’Day draw quite heavily on an article written by Brendan Bradshaw, ‘Nationalism and Historical Scholarship in Modern Ireland’ (first published in Irish Historical Studies, vol.26). For the most part their summary of his arguments are accurate. However, on page 9 they write:

The difficulty of being at once a professional historian, engaged with these issues, and a political polemicist, deeply committed to a special interpretation of the past, can be illustrated again by Brendan Bradshaw’s dual role, as nationalist and Catholic polemicist, and as professional Cambridge historian. As the former, Bradshaw has gone so far as to insist that the popular perception of Irish history constituted a ‘beneficent legacy – its wrongness notwithstanding’, andeven to demand the reinstatement of ‘the popular perception of Irish history as a struggle for the liberation of “faith and fatherland” from the oppression of the Protestant English’. (emphasis added)

Essentially, they suggest in quite strong terms (insist, demand) that Bradshaw advocates the popular, nationalist version of history. In the footnote they cite as the source for these quotations only his article mentioned above. So I went back to it for a closer look. Now I haven’t read Bradshaw’s other historical works, but based on my reading and understanding of the article in question, they quite blatantly misquote, misread, and misrepresent his arguments. For the first quotation they give, the full sentence Bradshaw actually wrote is:

In a nutshell, the issue raised by Butterfield’s exposition of the positive values of English public history [in The Englishman & His History and The Whig Interpretation of History] is whether the received version of Irish history may not, after all, constitute a beneficent legacy – its wrongness notwithstanding – which the revisionists with the zeal of academic pursuits are seeking to drive out.

He does not say, as Boyce and O’Day suggest, that ‘the received version of Irish history’is definitively a beneficent legacy. He says that the issue is whether it is and his statement hinges on that word, making it something entirely different than the way Boyce and O’Day quote it.

The second part of what Boyce and O’Day write relates to the ‘reinstatement’ of the preeminence of popular, nationalist history. However, a very basic problem is that this quotation does not come from the article cited at all. It comes from a different article by Bradshaw, titled ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’ (Fortnight, no.197, 1991), which they fail to mention in their footnotes. In the context of that article, Bradshaw addresses the combination of empirical skepticism and the whig interpretation of history in the revisionist project:

The practical consequence of this combination was a determination to debunk the popular perception of Irish history as a struggle for the liberation of “faith and fatherland” from the oppression of the Protestant English. On the contrary, the implications of my own insight seemed to be that “national consciousness”, comprised of precisely those elements, lay at the heart of the historic “Irish problem”.

I think few would disagree with his assessment of the revisionist focus on challenging national myths and the narrative of rebellion against 800 years of oppression by the English. He suggests not that these ideas should be reinstated, but that their significance and relevance within Irish history should be recognized. Whether or not the nationalist version of history is in any way accurate, many people believed in it and we cannot understand Irish history without some discussion of nationalism. Thus, far from arguing that Bradshaw is an incontrovertible nationalist, after this bit of historical detective work I would tend to agree with his own assessment of the article ‘Nationalism and Historical Scholarship’ as much closer to a post-revisionist manifesto than a nationalist one. And as much as this sort of detective work can have its rewards (I can’t deny getting some satisfaction from the ability to call out the mistakes of established scholars) let there be one lesson: always properly cite your sources! In this day and age all Sherlock Holmes needs is Google (and access to JSTOR).

I confess: I’m doing a Ph.D. in Digital Arts & Humanities. I also confess that when I’m asked what my Ph.D. is in I say History. Why? Because that’s my research area and at least people have an idea what history is. (Alright, sometimes the wrong idea – ‘Oh so you must remember loads of dates and stuff, right?’ Wrong. – But an idea nonetheless.) On a related note, I’m not yet convinced that digital humanities is actually a field of study rather than an umbrella term for a set of methodologies and beliefs shared across many fields. The third part of my confession relates to the aims and program of the digital humanities. Yes, I certainly think that new technologies can make a positive contribution to the types of research questions we ask in the humanities, the ways that we ask them, and processes of teaching and learning. However, I confess I find myself rather less than enamored by the way many scholars promote these goals in speeches and articles. Therefore I say I’m a skeptic not because I believe DH has nothing to contribute, but because I remain uncertain of the manner in which that contribution comes to force.

This post was prompted by reading Alan Liu’s article, ‘The State of the Digital Humanities: A Report and Critique’ (Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, Dec. 2011). Like many other articles on the status or definition of digital humanities, the reader gets the impression that he preaches to the converted, beginning with the very assumption that it is indeed a scholarly field and therefore merits attention as such. Another indicator of the fact that he speaks to those already familiar with the area is his excessive usage of what we might call ‘jargon’ (but Liu’s own research is in literary theory, so perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised by this). This type of language can have the detrimental effect of scaring off scholars who might otherwise express interest in what digital humanities has to offer. All DH scholars seem to expect the continued growth of the area, probably rightly so considering technology’s continued permeation of everyday life, but if the goal is for digital humanities to ultimately become synonymous with humanities in general and we don’t want to wait for a generation or two to go by for that to happen, then talking with and to current scholars (and the wider public) in practical terms that resonate with them would probably be a good idea.

For example, my first experience in digital humanities (though I knew nothing of that phrase at the time) was as an assistant/intern working with both the IT and History departments and my high school for three summers when I was in college. I’m not a tech-geek by any standards, but got on well with people from both departments and could therefore serve as a liaison between them. At the time, the school was adopting a one-to-one tablet laptop program and the history faculty wanted assistance figuring out how they could cope with and utilize the laptops in their classrooms. These are some of the best teachers and most intelligent people I know, but for some reason many found themselves intimidated by their own unfamiliarity with the technology. What scared them was not the fact that the students might draw maps digitally rather than on paper with colored pencils or the concepts built into a program such as Photoshop or the fact that the students might know more about the technology than they did, but the words. What does it mean if someone tells you to create a new layer in Photoshop and you’ve never used the program before? Very little. But start by saying that a layer is like a transparent sheet on top of the image so you can draw without affecting what’s underneath and it might click. The concepts behind much of the work in DH are straightforward and connected to those already present in the humanities generally, but start using acronyms and technical terminology and you lose a lot of people very quickly because it may not be clear to them if the time or effort it takes to figure out the technicalities just to get to the basic message will prove worthwhile.

Another aspect of Liu’s article that struck me is his discussion of the scale of digital humanities projects and the idea that they are constantly getting bigger. He writes, ‘scale is a new horizon of intellectual inquiry’, that all scholars should be able to access and analyze all the world’s digital information from anywhere; a lofty ambition indeed. This struck me as remarkably similar to the early emergence of social history – the ‘social’ aspect came to mean something covering the diversity of lived experiences (broadening the focus of the historical discipline to realms beyond the political and elite). Those associated with French Annales school of thought expressed the ambition to write ‘total history’, to capture all the variety of life. However, in practice historians came to understand that this could only fully take place on a relatively small, local scale. Though Liu mentions the Annales in the critique portion of his article, the second part of the realization of scale within social history seems to have failed to dawn on him. Big fish have their place, but in studying the whole ecosystem the small fish also deserve a mention.

To avoid ending the article on an entirely negative or critical note, I have a counter-proposal for the propagation of the digital humanities (whether or not we actually call it a ‘field’). First, preach to the unconverted in clear terms. In this regard, I think Ted Underwood’s article ‘On the Digital Humanities’ and the Journal of American History article/dialogue ‘Interchange: The Promise of Digital History’ (Sept. 2008) are much better places to start than Liu’s piece. Secondly, focus on smaller-scale applications of tools and methodologies. Make it clear how individual scholars or small groups with limited resources can gain from and contribute to the digital humanities, because they all have something to offer. Maybe once these issues take greater precedence I’ll become less of a skeptic.

The last two days (28-29 Sept. 2012) I attended the Oral History Network of Ireland conference in Ennis, Co. Clare. The organization was set up about two years ago and aims to bring together all sorts of individuals and groups across Ireland who work with oral history. In this way it was somewhat unusual for a conference as a large part of the audience came from outside academia, but there were many interesting presentations and discussions.

On the first day three different workshops were offered and I attended the one given by Maura Cronin on ‘using and interpreting oral sources.’ Issues covered included interviewing techniques, organizing collected material, transcription, and the interviewer/interviewee relationship. She also discussed the challenges of teaching oral history to undergraduates and having them collect material. However, these experiences seem to have negatively impacted her opinion of students’ capabilities and she continually referred to ‘young people’ in a somewhat derogatory fashion, which frustrated me. Yes, I agree that unfortunately undergraduates often have little motivation or interest in the subjects they study and sometimes they may not fully comprehend the stories told to them by elderly informants, whereas someone closer in age might pick up on ‘cues’ or ask better questions. However, in my own case I have found that being ‘young’ (or often at least 40 years younger than most of my informants) can have advantages. The interviewees do not assume I know what they are talking about and therefore are more likely to explain what life in the past was like and how it differed from today. I am not saying that either a smaller or larger age gap between interviewee and interviewer is necessarily good or bad, but that in either case it can have an impact on the social relationship and narrative that should be recognized. As historians we would not gather oral history interviews if we knew everything about the past already – we go out to talk to people because the subjects have something we want to learn about that is often inaccessible by other means.

On Friday evening Alessandro Portelli, a giant in the world of oral history, gave a wonderful keynote address, ‘They Say in Harlan County’, based on his recent book of that title. He framed his speech with his own experience of research in Harlan County and the relationship between oral historians and subjects – when he decided to go there first a former girlfriend told him not to because ‘they kill sociologists there’, but he went anyway. He found a community frustrated with being over ‘sociologized’ and ‘folklorized’, one that ‘is both a real place and a place of imagination’ because it has come to symbolize so much in the history of labour relations in the US. He said, ‘what I bring to the conversation is my ignorance’: he went to learn about the place, its history, and its people, not with preexisting notions of what it meant or what he would find. In return, he formed many valuable relationships and friendships with the people he met during many visits over more than 30 years. This mutual respect definitely shone through in his speech. I am looking forward to reading the book!

Two other papers particularly stand out in my mind, not so much because of content, but because of a very similar special respect and relationship expressed between the authors and interviewees. Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire spoke about his research on Dublin’s restaurants and culinary history, which was motivated initially by stories he heard from a teacher and mentor and the realization that no one else had or would collect those stories. His passion for the people, food, and material culture was palpable. (His PhD dissertation is available online and he is involved in the Gastronomy Archive at DIT.) The other presentation that stood out was Brenda Ní Shúilleabháin’s on arranged marriages in Corca Dhuibhne, using film footage from her documentary work. These clips were very personal and many quite humorous. She came to the conclusion that arranged marriages can work if they are accepted and supported by the society. Of the examples she showed, some women entered into them and were happy, while others chose to emigrate rather than face that situation. She also wins the award for best quote of the conference: when asked by a colleague about a particular story, ‘is it true?’, she responded ‘it’s in the parish of truth!’

Many common themes also emerged from the presentations: gender, migration, work, religion, and conflict. And common questions: What is ‘true’? Is memory individual or collective? What do people remember and why? How and for what purpose does the researcher ask them to remember? What do we hear? What ‘duty of care’ does the researcher have for the interviewee and his or her memories? There are no obvious answers to any of these, but it was refreshing to hear that all oral historians of all ages and levels of experience raise and struggle with them.