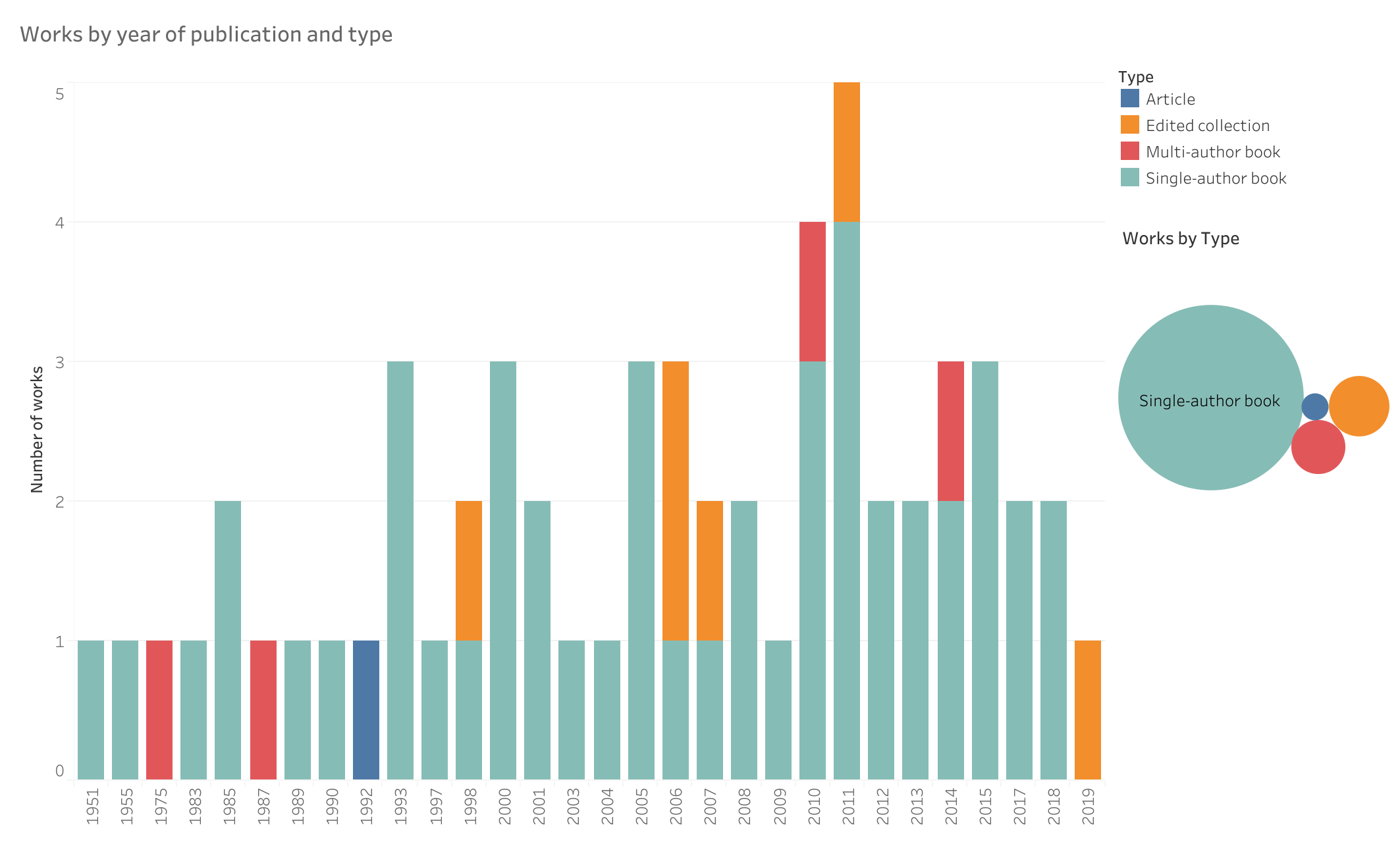

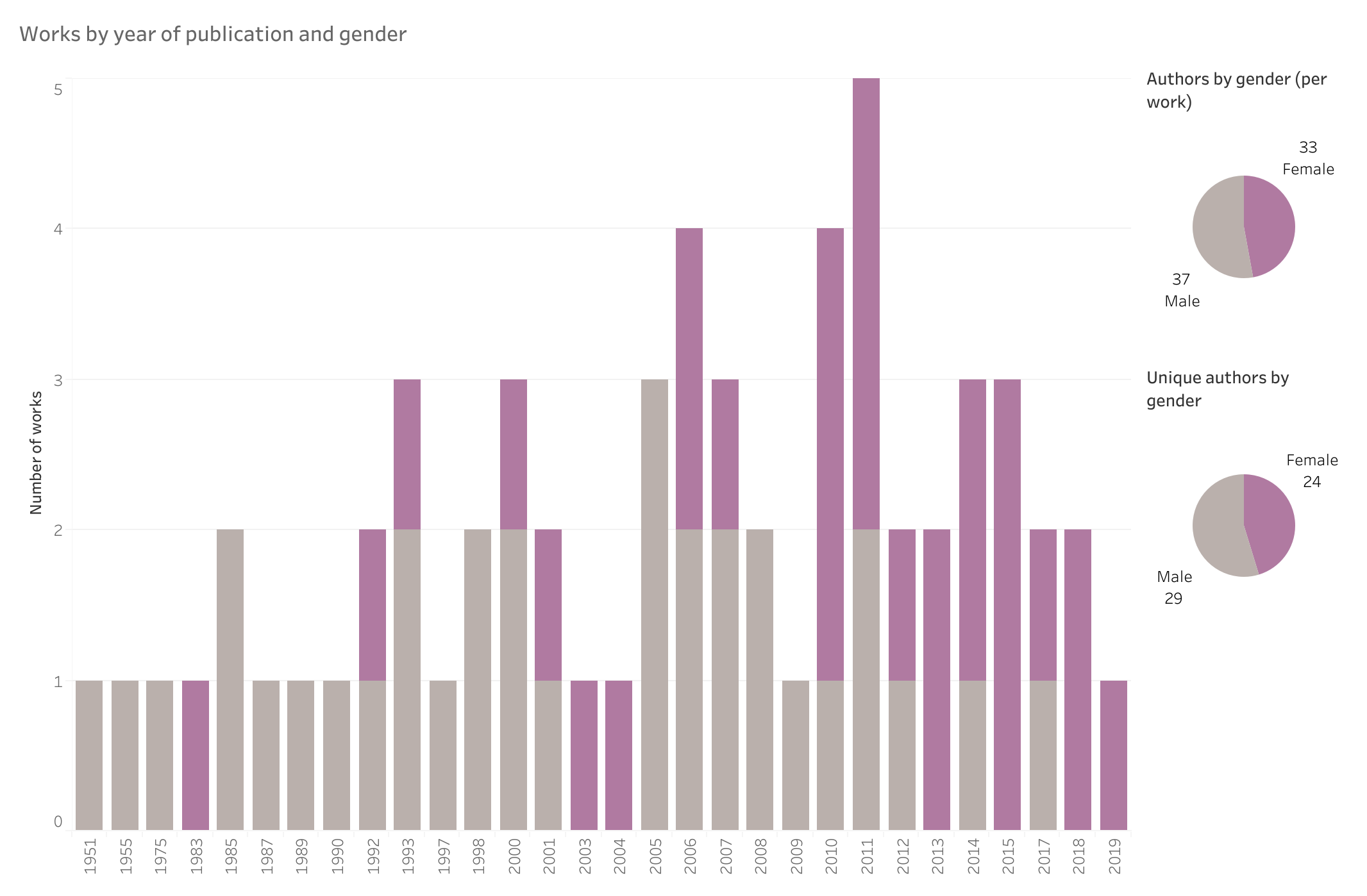

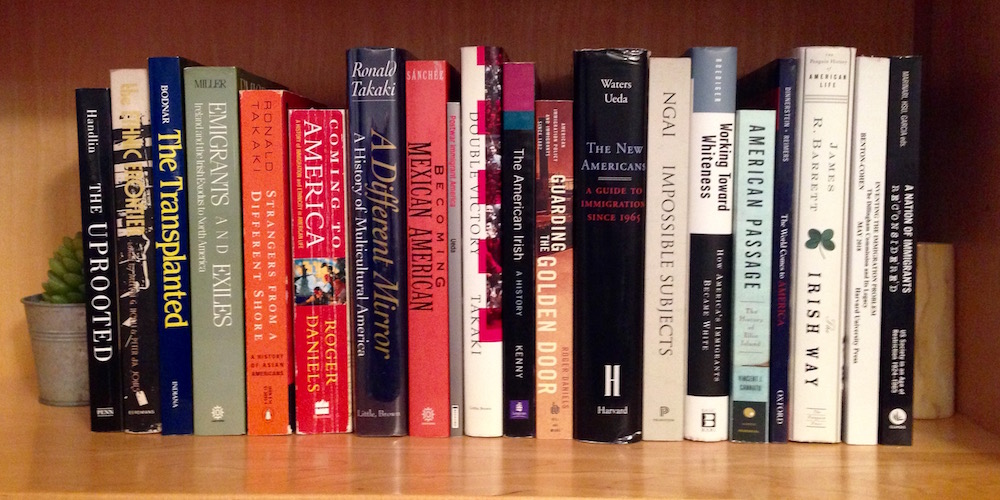

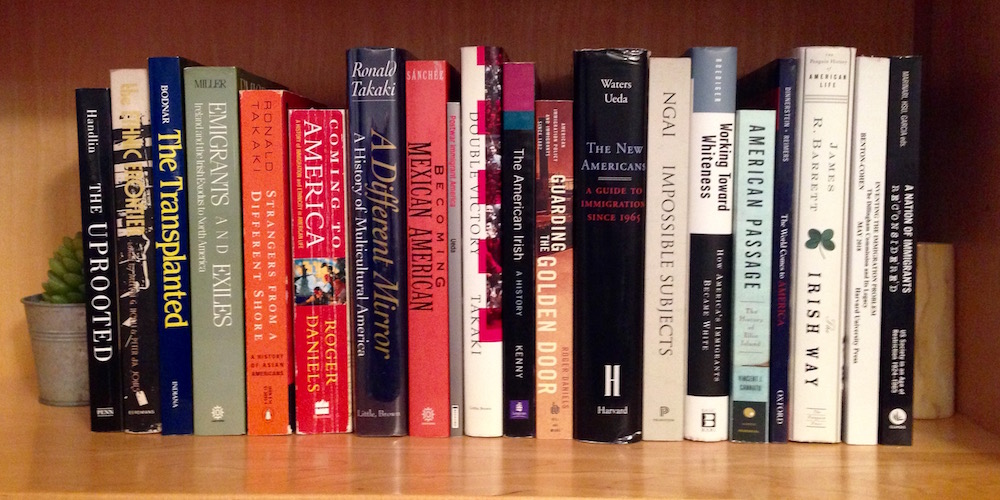

Fellow historians: I would like your input. I am writing a bibliographic essay on American immigration history (mid-nineteenth century to the present) for an audience of academic librarians. The basic assignment is to cover 50 books in 5,000 words. What follows is a draft list of 52 books, organized thematically into three categories. Note that the focus is monographs, not articles (though I may end up including a few of those).

Am I missing a book you consider crucial? What other text(s) would you include and why? If you would include another text, which one(s) from the current list would you leave out? Please share your thoughts in the comments.

Historians: Conceptualizing Immigration

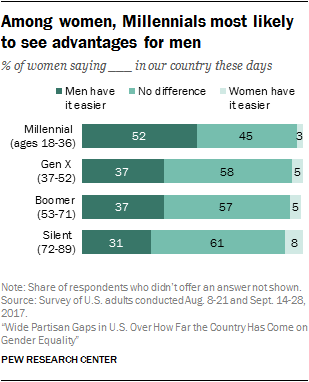

This section will outline trends in the historiography of American immigration, from Handlin to the present.

Bodnar, John, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1985).

Daniels, Roger, Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life, 2nd edition (New York: Harper Perennial, 2002).

Dinnerstein, Leonard & David M. Reimers, Ethnic Americans: A History of Immigration, 4th ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999).

Donato, Katharine M. & Donna Gabaccia, Gender and International Migration from the Slavery Era to the Global Age (Russell Sage, 2015).

Gabaccia, Donna, Foreign Relations: American Immigration in Global Perspective (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012).

Handlin, Oscar, The Uprooted: The Epic Story of the Great Migrations That Made the American People, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

Jacobson, Matthew Frye, Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998).

Marinari, Maddalena, Madeline Y. Hsu & Maria Cristina Garcia (eds.), A Nation of Immigrants Reconsidered: US Society in an Age of Restriction, 1924-1965 (Urbana, Chicago & Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2019).

Molina, Natalia, How Race Is Made: Immigration, Citizenship, and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014)

Reimers, David, Other Immigrants: The Global Origins of the American People, (New York: New York University Press, 2005).

Roediger, David R., Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White (New York: Basic Books, 2005).

Takaki, Ronald, A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America (Boston: Little Brown & Company, 1993).

Ueda, Reed (ed.), A Companion to American Immigration (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2006).

Yans-McLaughlin, Virginia (ed.), Immigration Reconsidered: History, Sociology, and Politics (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990).

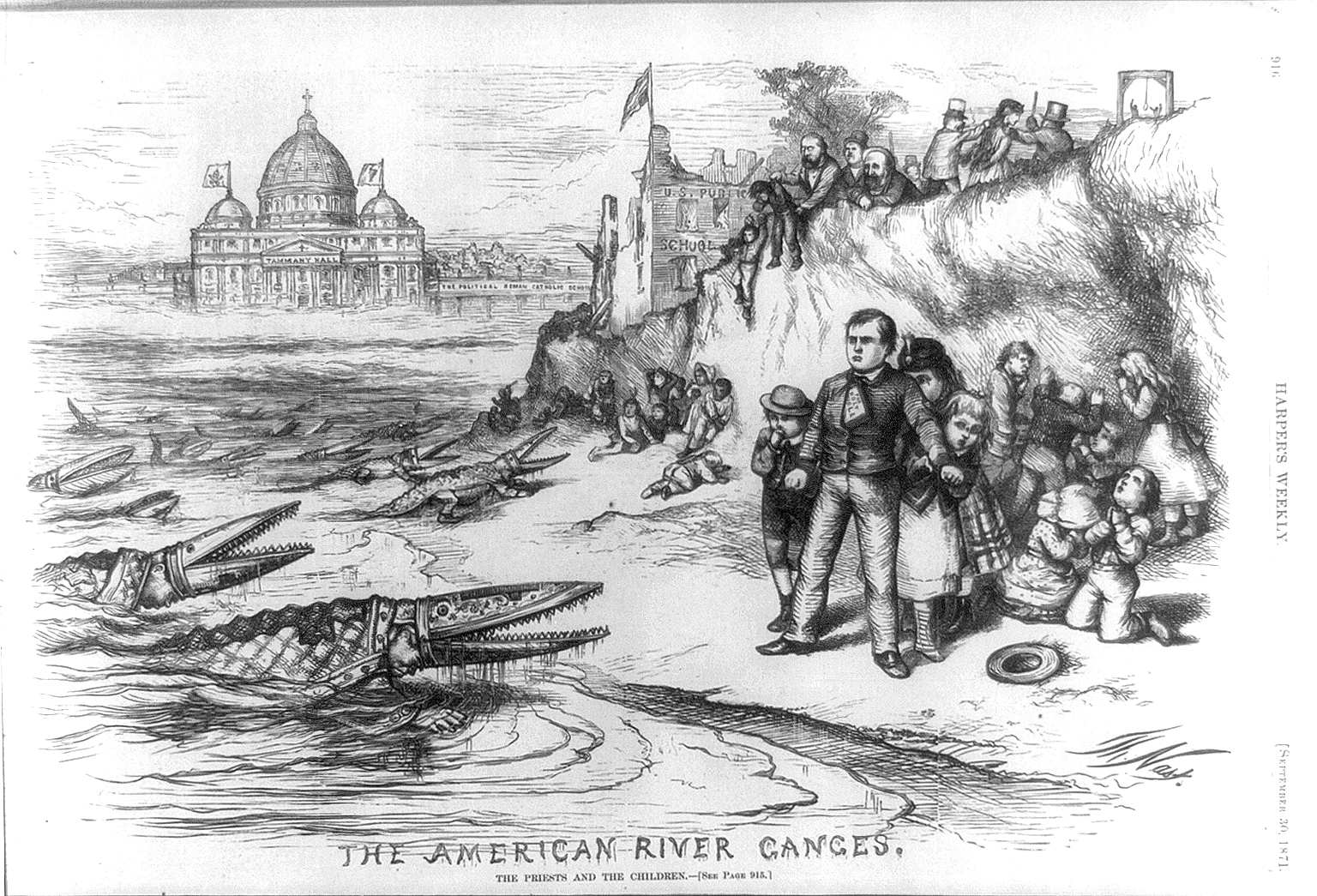

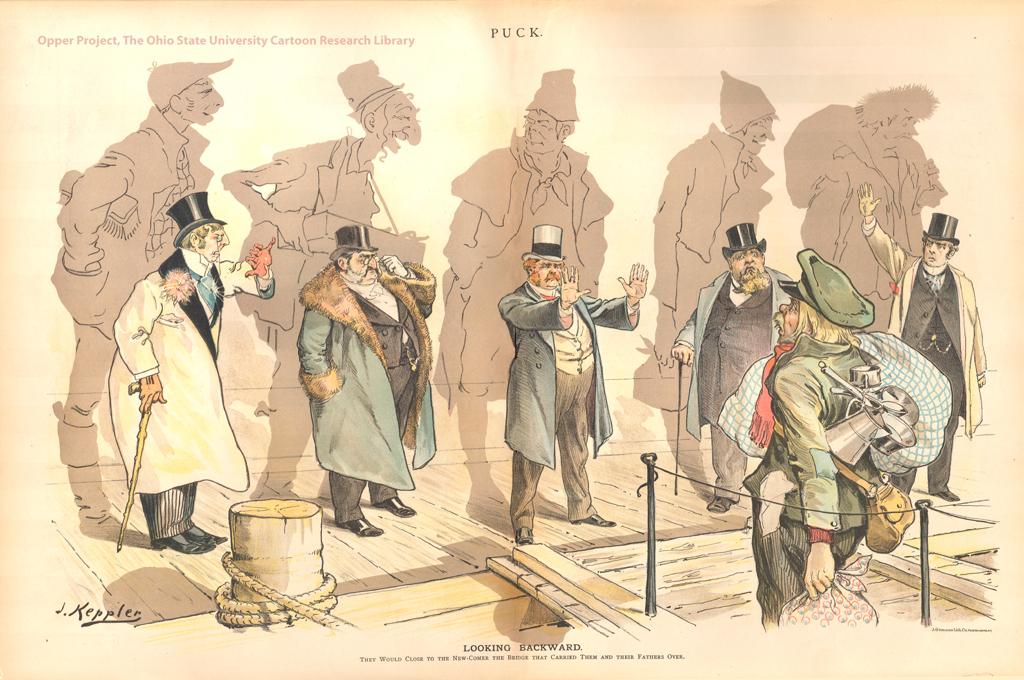

Americans: Controlling Immigration

This section will focus on law, policy, and ideologies related to immigration and how those have evolved over time.

Benton-Cohen, Kathleen, Inventing the Immigration Problem: The Dillingham Commission and Its Legacy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018).

Bon Tempo, Carl J., Americans at the Gate: The United States and Refugees during the Cold War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008).

Brown, Wendy, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (New York: Zone Books, 2010).

Cannato, Vincent. American Passage: The History of Ellis Island (New York: Harper Perennial, 2010).

Daniels, Roger, Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2005).

Ettinger, Patrick, Imaginary Lines: Border Enforcement and the Origins of Undocumented Immigration (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009).

Haines, David W., Safe Haven?: A History of Refugees in America (Sterling, VA: Kumarian Press, 2010).

Higham, John, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925, 2nd ed. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988).

Hirota, Hidetaka, Expelling the Poor: Atlantic Seaboard States and the Nineteenth-Century Origins of American Immigration Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

Kang, S. Deborah, The INS on the Line: Making Immigration Law on the US-Mexico Border, 1917-1954 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

Law, Anna O., The Immigration Battle in American Courts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Lee, Erika & Judy Yung, Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Luibhéid, Eithne, Entry Denied: Controlling Sexuality at the Border (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

Lytle Hernandez, Kelly, Migra!: A History of the US Border Patrol (Oakland: University of California Press, 2010).

Ngai, Mae, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004).

Schrag, Peter, Not Fit for Our Society: Immigration and Nativism (Berkeley: University of California Press, Berkeley, 2011).

St. John, Rachel, Line in the Sand: A History of the Western U.S.-Mexico Border, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2013.

Immigrants: Lives, Cultures & Communities

Of the three sections, I had the most difficulty limiting the number of texts in this one. Overall it is intended to cover a broad range of ethnic and racial groups, geographies, and cultural practices. The texts represented here should be the definitive texts on their subject and/or representative of recent trends in scholarship on that subject.

Barrett, James R., The Irish Way: Becoming American in the Multiethnic City (New York: Penguin Press, 2012).

Choate, Mark I., Emigrant Nation: The Making of Italy Abroad (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008).

Diner, Hasia R., Roads Taken, The Great Jewish Migrations to the New World and the Peddlers Who Forged the Way (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2015).

Gabaccia, Donna R., We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000).

Gjerde, Jon, The Minds of the West: Ethnocultural Evolution in the Rural Middle West, 1830-1917 (University of North Carolina Press, 1997).

Gutiérrez, David G., Walls and Mirrors: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the Politics of Ethnicity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995).

Halter, Marilyn & Violet Showers Johnson, African & American: West Africans in Post-Civil Rights America (New York & London, New York University Press, 2014).

Hansen, Karen V., Encounter on the Great Plains: Scandinavian Settlers and the Dispossession of Dakota Indians, 1890-1930, Oxford University Press, 2013.

Hsu, Madeline Y. The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015).

Kenny, Kevin, The American Irish: A History (Harlow, UK & New York: Longman, 2000).

Lee, Erika, The Making of Asian America: A History, Simon & Schuster, 2015.

Lee, Joseph & Marion R. Casey (eds.), Making the Irish American: History and Heritage of the Irish in the United States (New York: New York University Press, New York, 2006).

Lorenzkowski, Barbara, Sounds of Ethnicity: Listening to German North America, 1850-1914 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2010).

McBee, Randy, Dance Hall Days: Intimacy and Leisure among Working-Class Immigrants in the United States (New York & London: New York University Press, 2000).

Miller, Kerby A., Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Minian, Ana Raquel, Undocumented Lives: The Untold Story of Mexican Migration (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018).

Sánchez, George J., Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

Showers Johnson, Violet, The Other Black Bostonians: West Indians in Boston, 1900-1950 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006).

Takaki, Ronald, Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans, revised edition (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1998).

Waters, Mary C. & Reed Ueda (eds.), The New Americans: A Guide to Immigration since 1965 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007).

Young, Elliott, Alien Nation: Chinese Migration in the Americas from the Coolie Era through World War II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

Zahra, Tara, The Great Departure: Mass Migration from Eastern Europe and the Making of the Free World (W.W. Norton & Company, 2016).

Please share your thoughts in the comments below or contact me directly. Thank you!