A House Divided

If this was clickbait, the headline might be “Is America More Polarized Than Ever?” But I dislike clickbait and especially titles with questions in them. Discussions of polarization in American political life seem to be trending. Nonetheless, while our society may feel more polarized now than in recent decades, taking a longer view calls that claim of exceptionalism into question. Since the nation’s founding, Americans have disagreed, at times violently, over political issues. The Civil War, the Gilded Age, the Civil Rights era, the Vietnam War: all come to mind as examples of when society faced intense divisions. The intent here is not to define an objective benchmark against which to measure present polarization. Rather, history can inform our discussion of it, who it includes or excludes, and what we stand to gain or lose by attempting to lessen it.

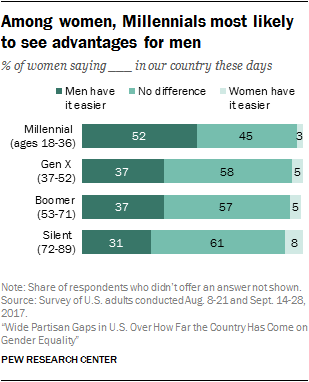

In Polarized: Making Sense of a Divided America, James Campbell defines polarization as “the condition of substantial and intense conflict over political perspectives arrayed along a single dimension — generally along ideological lines”.[1] If that is the case, then oppressed or marginalized people throughout American history must live in another dimension. They have existed, and continue to exist, largely beyond the the poles of power, which concentrates in the hands of the white, male, and wealthy, regardless of political party. The exclusion of women and people of color, despite their centrality to the nation’s history, is inherent in contemporary discussions of political polarization. Only as the poles shift and we see in more than one dimension — a black president, a female presidential candidate — do racism and sexism get described as “polarizing,” because they impinge on the status quo. White men in positions of power have a long history of claiming that they could represent the disenfranchised, from enslaved people under the 3/5ths compromise to women prior to suffrage. Insist otherwise, and suddenly the nation is “polarized”.

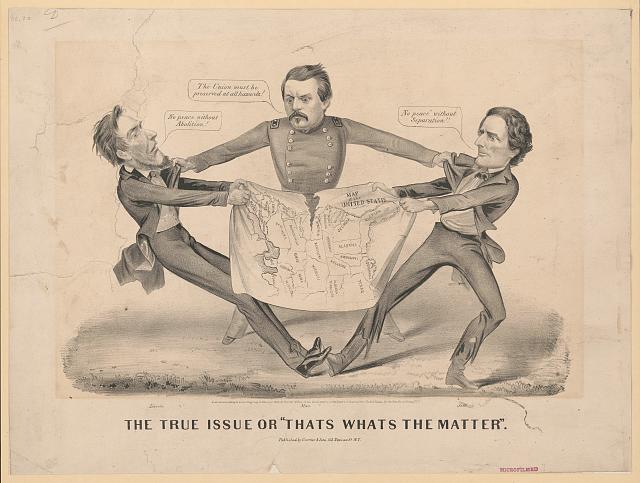

The Civil War era stands out as an extreme example of polarization with resonance today. A series of political compromises failed, and in 1858 the then Senate-candidate Abraham Lincoln asserted that “a house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. ” His election prompted southern secession and as president he would oversee a war to reunify the house without the stain of slavery. However, while no one conducted opinion polls of enslaved people, I highly doubt they were polarized over the issue of their freedom. That conception could apply only to those with a modicum of power.

The Civil War’s aftermath also leads to the question of what we may lose by returning to an agreed-upon center. In Race and Reunion, historian David Blight argues that achieving national reconciliation involved a tacit acceptance of white supremacy to bring the South back into the fold. Unity depended on historical amnesia, forgetting the true reason for fighting the war: slavery and emancipation. As Reconstruction failed and segregation deepened, the nation found it more comfortable to believe that the Second American Revolution had completed what the first had not and created a unified nation.

Though Blight focuses on how historical memory evolved in the fifty years after the war, it’s possible to see the later ramifications of this process. Many Americans still seem to think it’s up for debate whether slavery caused the Civil War. It’s not. The historical consensus is well established on that front. The persistence of the myth of the Lost Cause and nobility of “both sides” was the price paid for national reconciliation. The continued ‘debate’ over insidious racism in American society is a price we still pay. As Blight wrote more recently, “not only is the Civil War not over; it can still be lost.”

None of this is to say that contemporary divisions do not exist or do not matter. Rather, seeing contemporary America as uniquely divided rests upon a particular vision of history, one that has more in common with myth than reality. The stable world imagined to have existed in the past (presumably back when America was “great”) was built upon silencing and oppression. It was a world “more devoted to order than justice”. While social media has given more people today a voice, the power to be heard remains unequally distributed along intersecting lines cut by class, race, and gender. The only comfort, perhaps, is that those resisting systems of oppression can tell their own stories, and those stories matter. The poles can only shift if pushed, and they still may shift back again. History is not linear. Progress is not predestined.

Lincoln predicted, “I do not expect the Union to be dissolved — I do not expect the house to fall — but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.” The reality, which he did not live to see, proved more complicated. There are questions we still need to confront: What price will we pay for the perception of unity? Do we want “balance” (in the media, in politics) if that means normalizing extremism? Or, can we move beyond partisan outrage and the politics of resentment? Can we hold our society accountable to the truths of history? How can we ensure that more voices are heard, and valued? Can we foster empathy and build on it to create meaningful change? What might that look like?

Following the recent midterm elections, Nancy Pelosi said “we have an obligation to try to find common ground”. As the 116th Congress prepares to take their seats, it remains to be seen whether they will usher in an era of greater or lesser polarization. What may be the price of unifying our house now?

These questions have no easy answers. We need to ask them regardless, and repeatedly. And we need to insist on answers that may not be answers at all, but that embrace complexity. Any form of reconciliation in the present will depend on reckoning with past wrongs, not on the papering over them. We cannot avoid arguments, because “America is an argument”.[2] What we can do is strive for better conversations and better journalism. Clickbait will not save us now.

—

[1] James E. Campbell, Polarized: Making Sense of a Divided America (Princeton University Press, 2016), p.16.

[2] Liu’s article prompted the development of the Better Arguments Project, which provides one possible model for more meaningful civic engagement.