Postcards from the Road

Commonplace artifacts of material culture since the late nineteenth century, postcards are cheap to produce, purchase, and mail, they don’t require much personalization, and sending them to family and friends can make others jealous of the interesting places you visit. Often they depict beautiful landscapes or historic sites, which is why, looking through a collection my mom kept growing up, I was surprised to find several postcards of highways.

Seriously, who sends postcards of highways?

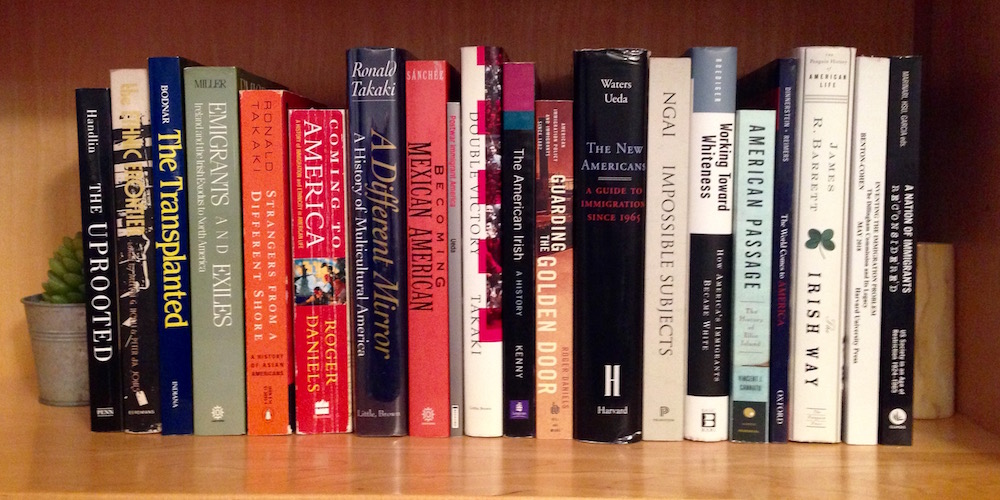

To viewers, postcards structure “how and what views were to be taken from a rapidly changing world,” and their publishers often marketed the future those changes represented.[1] In the US after World War II, that included expanding infrastructure and mass consumerism. While highway construction had begun in the 1920s, it took off in the 1950s, characterized by “limited-access roads”: standardized, four (or more) -lane highways with interchanges. The prototype, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, first opened in 1940 and was completed by 1954. Its popularity exceeded expectations, making it a model for the 41,000 miles of the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways developed under the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. This massive federal investment in infrastructure represented the largest public works project ever undertaken and spurred economic growth.

Increased highway construction, suburban sprawl, urban redevelopment, and car ownership all intertwined in the prosperous postwar decades. Together they created the car-centric “landscape of mass consumption” most Americans experience today.[2] This has had a profound impact on where we live and work, and spend our free time. In the postwar decades more families purchased cars and traveled further in them, making recreational travel a central part of middle-class culture and an expression of affluence.[3]

Enter the roadtrip. What to Americans in 2020 seems retro was novel to Americans in 1965. Postcards of highways highlight that novelty, and they marketed it. The highways pictured are remarkably empty. These are open roads, an uncommon sight today, and, since traffic rapidly increased after their construction, an uncommon sight at the time too.

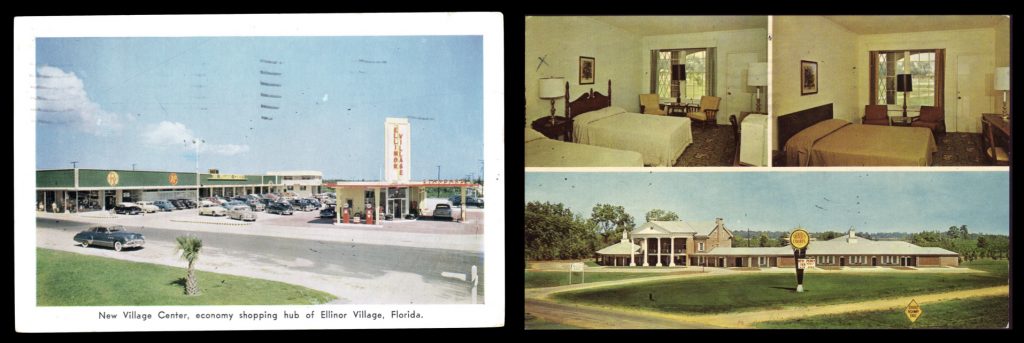

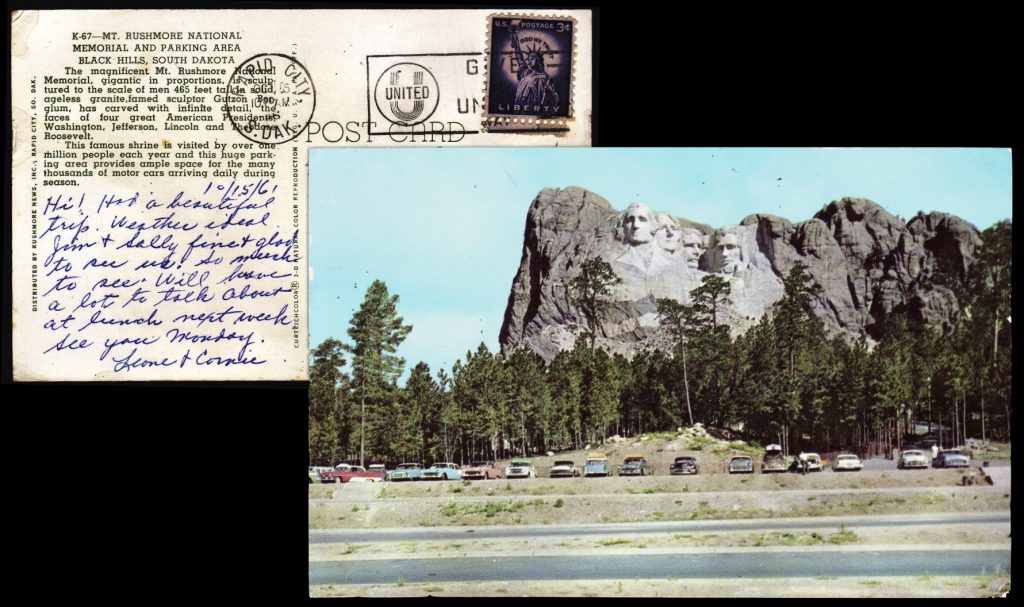

As the highway system expanded, so did roadside attractions from shopping centers to motels (from “motor hotels”). They boasted ample parking to cater to their customers. Historical sites adapted too, expanding their parking lots and advertising their convenience, as in the postcard from Mount Rushmore below.

Postcards tend to set a positive tone. They leave out a lot: the political and social upheavals of the era; the communities and ecosystems that highway construction destroyed; and the many Americans denied access to prosperity. In some ways these things feature implicitly: the Georgia motel built in 1963 in “plantation revival” style suggests who would, and who would not, be welcome guests. A postmark from 1954 reads “hire the handicapped – it’s good business,” a record of a government campaign in the history of Americans with disabilities.

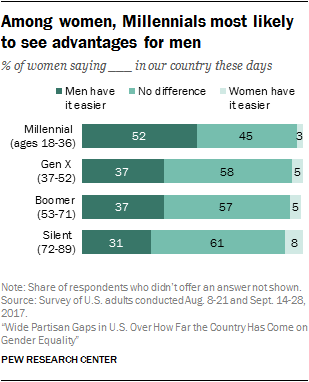

Gendered histories also surface here: many of the postcards in the collection I’ve drawn from came from female colleagues of my grandmother. They suggest ways women created bonds in male-dominated workplaces. However, the majority of the postcards sent to the whole family were addressed to my grandfather “& family” or “& co.”. A woman’s ambitions in this era – my grandmother left her home in Ohio to take a job three states away – were nonetheless subsumed by her marital and maternal role.

Owning a car and taking to the “open road” represents a peculiarly American sort of individualism. Yet ironically its expression depends upon the interstate highways created with federal funds. Americans celebrated that public infrastructure in images shared via another key public service, the USPS. Perhaps it’s time we remembered that.

[1] John A. Jackle & Keith A. Sculle, Picturing Illinois: Twentieth Century Postcard Art from Chicago to Cairo (University of Illinois Press, 2012), 21, 186.

[2] Lizabeth Cohen, A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (Knopf, 2003), 13; Christopher Wells, Car Country: An Environmental History (University of Washington Press, 2013).

[3] Susan G. Davis, “Time Out: Leisure and Tourism,” in Jean-Christophe Agnew & Roy Rosenzweig (eds.), A Companion to Post-1945 America (Blackwell Publishing, 2002), 68.