The Value of the Humanities

I was asked recently to make an argument for the value of the humanities, a challenge given the amount of ink already spilt on the subject. Some authors frame it in positive terms, articulating the usefulness of the field. Others bemoan its perceived state of crisis. I would like to avoid whining about why no one appreciates us humanists anymore and focus on the positive. For me, the value of the humanities lies in the space they give us for reflection on the human condition.

Being Human

This is part of a larger question: what does it mean to be human? Anytime I visit a new city I make a point of visiting bookstores, particularly used bookstores. On a trip to Kansas City about a month ago I picked up a copy of Eduardo Galeano’s Mirrors: Stories of Almost Everyone. It comprises a series of vignettes, short prose-poems, on subjects from across world history. One of my favorites is titled “Only Human”:

Darwin told us we are cousins of the apes, not the angels. Later on, we learned we emerged from Africa’s jungle and that no stork ever carried us from Paris. And not long ago we discovered that our genes are almost identical to those of mice.

Now we can’t tell if we are God’s masterpiece or the devil’s bad joke. We puny humans:

exterminators of everything,

hunters of our own,

creators of the atom bomb, the hydrogen bomb, and the neutron bomb, which is the healthiest of all bombs since it vaporizes people and leaves objects intact,

we, the only animals who invent machines,

the only ones who live at the service of the machines they invent,

the only ones who devour their own home,

the only ones who poison the water they drink and the earth that feeds them,

the only ones capable of renting or selling themselves, or renting or

selling their fellow humans,

the only ones who kill for fun,

the only ones who torture,

the only ones who rape.

And also

the only ones who laugh,

the only ones who daydream,

the ones who make silk from the spit of a worm,

the ones who find beauty in rubbish,

the ones who discover colors beyond the rainbow,

the ones who furnish the voices of the world with new music,

and who create words so that

neither reality nor memory will be mute.[1]

Humans are capable of expressing both extraordinary cruelty and extraordinary beauty. The humanities seek to make sense of that through culture. But it is not only an academic endeavor. It is about finding meaning in our existence.

That act is not limited to the present, nor to a single place. Galeano’s book turns western history on its head, juxtaposing world religions, philosophies, and scientific discoveries. Confronted with these “stories of almost everyone” – like hand stencils in cave paintings – we cannot escape a sense of shared humanity, no matter the distance across space or time.

Context

The humanities teach us about being people. They provide context for our lives and societies. History forms a key part of this (though as a historian no doubt I’m biased in this regard). I would like to illustrate it with an example relevant to contemporary discourse: immigration.

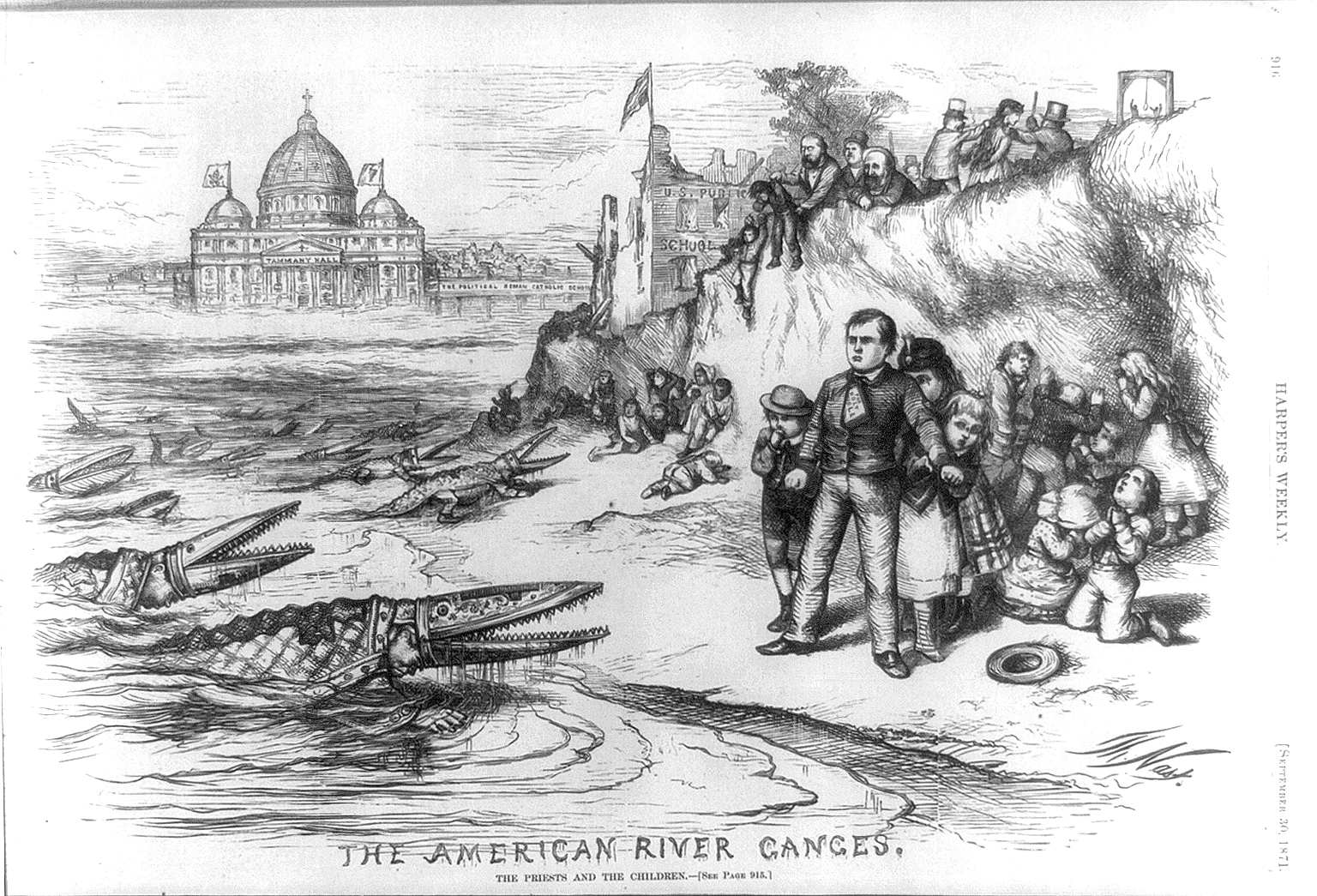

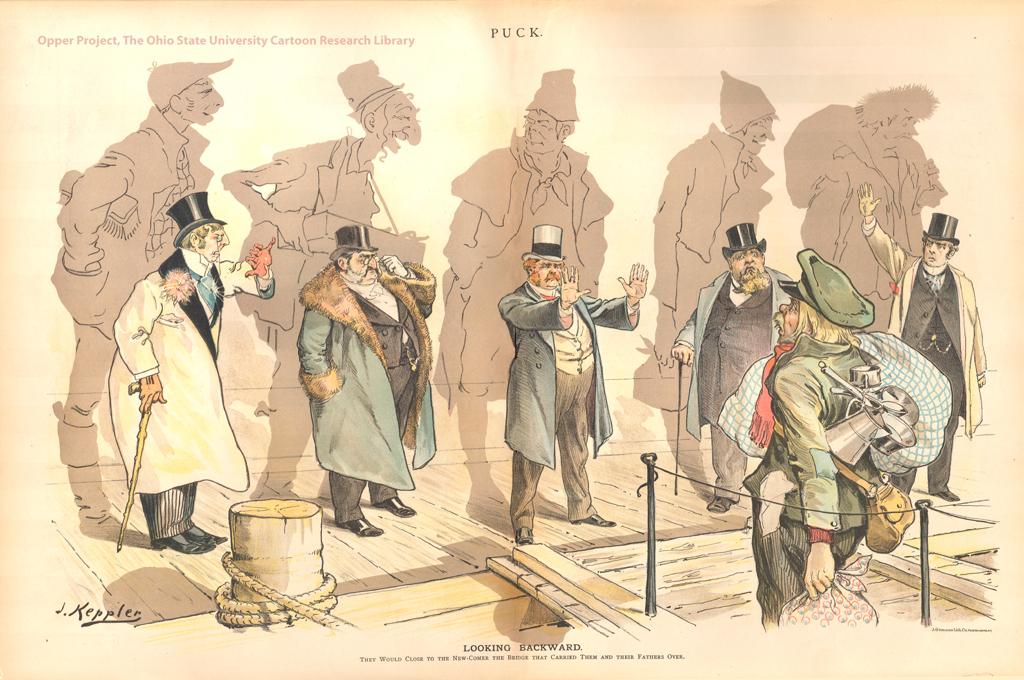

Across American history, nativists have targeted different groups of immigrants with the same types of rhetoric. In the 1750s, Benjamin Franklin complained about Germanic peoples and their failure to assimilate to Anglo-American life. From the 1840s fears were directed towards Irish Catholics, the poor huddled masses fleeing famine who, by virtue of their poverty and religion were seen as unintelligent and disloyal.

In the late nineteenth century the Chinese became the first racial or ethnic group specifically excluded by legislation, while more expansive restrictions in the early twentieth century focused on reducing immigration from eastern and southern Europe. War compounded anti-Asian sentiments and in the 1940s Japanese Americans were rounded up into camps (in the interests of national security, of course) despite no evidence of espionage. More recently the same types of rhetoric have been turned on Mexicans and Muslims.

The continuity across these examples is their basis in fear: fear of otherness (whether racial, ethnic, or ideological) and fear of people whose locus of loyalty might lie elsewhere.[2] The question of what it means to be American – and, therefore, who qualifies and who decides – is older than the nation itself. In all cases, Americans who are themselves descendants of immigrants are also those arguing against immigration, forgetting or denying the experiences of their own ancestors. This reflects the final lines of the Galeano passage above: we must know this history so that “neither reality nor memory will be mute”. My point here is not about knowing the facts of history, but in recognizing that everything has a history and history itself is contested, subject to both deliberate remembering and forgetting in the service of the present.

Education

The question then becomes, how do we educate people so that they develop reflective and critical perspectives on our society? Many articles advocating for the humanities in education make utilitarian arguments. They inundate readers with data about the employment or salaries of graduates with humanities degrees or lists of skills they may have learned, whether information literacy, writing, critical thinking, creativity, or empathy.

Without denying the importance of ‘transferable skills’ and the reasons for an evidence-based approach to humanities advocacy, economic arguments alone will not save the day. They form part of a general trend towards neoliberalism in education, particularly higher education, which sees students as consumers. Any aspect of the experience that lacks an obvious connection to a job is called into question.

However, if we understand education in the broadest sense as concerning more than a defined set of knowledge or marketable skills, then the humanities are valuable because they give us perspective. They contribute to an informed, democratic society. In the words of documentary filmmaker Ken Burns, “they liberate us from the myopia our media culture and politics impose on us”.[3] This can occur only when we have “the intellectual space to grapple with questions of enduring importance”:[4] questions of why the world is the way it is. As such, the value of the humanities extends beyond school. Education at every level should create learners who can participate in society in an informed way, whether through reading poetry or debating current events.

Around 1818 Caspar David Friedrich painted one of the quintessential images of European romanticism: The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. Using it as a metaphor, science (or the enlightenment rationality of the eighteenth century) might lead the wanderer to ask what lies under the fog, why the landscape takes a particular shape, what flora and fauna inhabit it, and what sort of particles hold it all together. Science, at its best, complements the humanities.[5] But if the wanderer is a humanist, then he might ask: what is his place in this landscape and why does it matter? Through the humanities we ask why, despite the short time we spend on this earth – less than the blink of an eye for the universe – we still need it to mean something.

The humanities remind us of our common bonds and give us the space to question their complexity. An education in the humanities is not a sugar-coating of idealism, but the realization that context matters, history stays with us, and there are no easy solutions. Despite 200,000 years of modern human life, we are still trying to figure it all out. No currency can measure the enduring value of that endeavor.

[1] Eduardo Galeano, Mirrors: Stories of almost Everyone, translated by Mark Fried (Portobello Books, London, 2009), pp.227-8.

[2] For more detail, listen to: The BackStory, “On the Outs: Restricting American Immigration” [radio/podcast], Feb. 10, 2017. http://backstoryradio.org/shows/on-the-outs/

[3] Ken Burns, NEH Jefferson Lecture, 2016.

[4] L.D. Burnett, “Holding on to What Makes Us Human: Defending the Humanities in a Skills-Obsessed University,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, Aug. 7, 2016

[5] Martha Nussbaum, Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities (Princeton University Press, 2010), p.8.